It is Illegal to be in possession of LIVE redfin perch.

Description & biology

Description: Redfin perch belong to the family Percidae. They can be recognised by the following features:

- a deep body and a slightly forked tail;

- two distinctly separate dorsal fins, the first with 12-17 strong spines and a distinct black blotch at the rear;

- a pattern of five or more broad black vertical bands across the back, tapering on the sides (more prominent in younger fish);

- bright reddish-orange pelvic and anal fins and tail.

The body colour varies from olive green to grey on the back, fading to greenish or silvery on the sides and whitish on the belly. While redfin perch can reportedly grow to 60 cm in length and around 4.8 kg in weight, specimens in NSW are mostly smaller, with 95% of fish less than 230 mm and 200 grams..

Habitat: Redfin perch live in a wide variety of habitats, but prefer still or slow-flowing waters such as lakes, dams, billabongs, swamps and slower moving streams and rivers. They prefer areas with good shelter such as snags (submerged dead wood and trees), vegetation or rocks, but have also been caught in open water.

Feeding: Redfin perch are carnivorous and feed on a wide variety of foods ranging from small invertebrates (such as crustaceans, worms, molluscs and insect larvae) to fish. They are known to hunt fish either solitarily (by ambushing or stalking their prey) or in organised groups. In groups, they herd shoals of small fish until encircled or pinned against the bank; a few of the redfin then chase into the shoal while the majority hold position and prey on fleeing fish. Schools of redfin perch also use a similar method known as “beating”, where they flush out insects and small fish from weed beds or other shelter into open water, where they become easy prey for waiting redfin perch. Such methods give them a reputation as voracious predators.

Reproduction: Redfin perch spawn in late winter and spring, when they lay several hundred thousand eggs in a gelatinous ribbon amongst aquatic vegetation, submerged logs or other sheltered areas. The egg mass is unpalatable to most other fish and is hence generally protected from predation. The eggs develop and hatch in about a week, and the young fish school to help avoid predation. Redfin perch usually take 2-6 years to reach sexual maturity, but some have been found to be reproductively mature at 1 year of age.

Where are they in NSW?

Redfin perch are widespread throughout much of the cooler waters of NSW and Victoria, particularly along of the Great Dividing Range. They are also known to occur in the ACT, south-eastern South Australia, Tasmania and south-western Western Australia. Their distribution seems to be limited by an upper water temperature of around 31°C and they are rarely found in fast-flowing waters.

In 2006 NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI) discovered populations of redfin perch in parts of the upper Lachlan, Abercrombie and Wollondilly catchments. These areas, which were previously free of redfin perch, support some of the last known populations of threatened native Macquarie perch and southern pygmy perch in NSW. In 2008, redfin were also discovered in Oberon Dam in the upper Macquarie catchment.

In early 2010 NSW DPI acted quickly on a report of redfin perch in a farm dam in the upper Hawkesbury-Nepean catchment, upstream from Coxs River and Lake Wallace. Redfin perch had not been recorded in the area previously and this sighting was considered to be a significant threat to Macquarie perch which is known to inhabit the Coxs River, while Lake Wallace is an important recreational impoundment for trout and bass.

NSW DPI with the assistance of local recreational fishing groups drained the dam to eradicate the redfin perch. The majority of the redfin perch were dispatched while some were collected from the dam and transferred live to Sydney University for research purposes. Nearby locations were subsequently surveyed for redfin perch in mid-2010, and none were found.

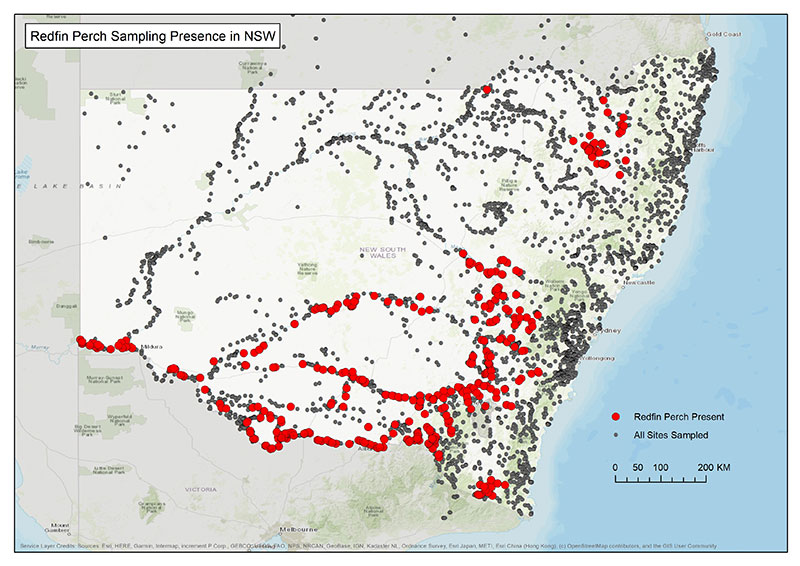

Known and probable distribution of redfin perch in NSW

NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development and its employees disclaim any liability for an act done on the basis of information in the map and any consequences of such acts or omissions.

How did they get here?

Redfin perch were first introduced to Australia in the 1860s for angling. Populations discovered in the upper Hawkesbury-Nepean, Lachlan, Abercrombie and Wollondilly catchments in the last two decades are likely to have been introduced deliberately, as they are geographically isolated from existing populations and could not have spread naturally. Please note that translocation (movement and release elsewhere) of any fish without a permit is illegal and heavy fines apply.

What are their impacts

Redfin perch are voracious predators which consume a wide variety of fish and invertebrates, including small native species such as pygmy perch, rainbowfish and carp-gudgeon, and the eggs and fry of larger fish such as silver perch, golden perch, Murray cod and introduced trout. Importantly, as redfin perch spawn several months earlier than native fishes (late winter to early spring), the large schools of predatory redfin perch fingerlings preying on hatching native fish larvae severely limit recruitment success of native fish.

This predation can seriously impact populations of native species and trout, and hence can also affect recreational fisheries for these species. For example, redfin perch were recorded as eliminating 20,000 newly released rainbow trout fry from a reservoir in south-western Australia in less than 72 hours. Redfin perch are capable of rapidly populating new waterways and in stable water bodies (such as lakes and dams) they can form very dense populations. Under these conditions, redfin perch become stunted as they deplete the food supply, becoming worthless for angling.

In such large numbers, they can also out-compete most other fish species.

Did you know redfin perch can spread disease?

One of the most significant threats to native fish from redfin perch is their potential to spread the viral disease Epizootic Haematopoietic Necrosis (EHN). This disease, which was first isolated in 1985 and is unique to Australia, can cause mass mortality in juvenile redfin perch during the summer months.

A number of native species, including mountain galaxias and particularly Macquarie perch, are highly susceptible to the disease, and EHN virus may be one factor responsible for the decline in various native species over the last couple of decades.

What is NSW DPIRD doing?

Redfin perch are listed as notifiable under the Biosecurity Regulation 2017. This listing recognises the threat that this species causes to native fish populations, and prohibits live possession and sale of the species. For more information on the listing of redfin click on the link below.

NSW DPIRD has ongoing survey programs across parts of NSW (primarily inland waters of the Murray-Darling Basin) which gather information on the distribution of freshwater fish species, including introduced pest fish such as redfin perch.

The department has undertaken specific surveys to confirm the presence and abundance of redfin perch in new areas. This will continue following reports of new incursions in other parts of the state.

NSW DPIRD has considered a range of options for targeted control and/or containment of redfin to limit the impacts on threatened species. As with all pest fish in open waterways, it currently appears to be very difficult to eradicate redfin perch populations or prevent natural dispersal to new areas.

Endangered southern pygmy perch and Macquarie perch were collected from sites under threat from redfin and held in captivity. For Macquarie perch, captive-bred fingerlings were released into a redfin-free tributary stream with a waterfall to prevent redfin colonisation. Attempts to ensure the long-term security of this new population are ongoing.

For southern pygmy perch, redfin perch exclusion barriers have been installed/maintained to prevent further upstream colonisation. southern pygmy perch have also been translocated into a number of farm dams across their distribution to protect them from redfin perch. And southern pygmy perch have also been translocated into neighbouring redfin perch-free tributary streams to protect populations.

Efforts to protect our native species also require the help of the public. NSW DPIRD undertakes regular awareness raising campaigns to alert anglers to the problems redfin perch can cause. For example the A4 double-sided poster “Keep Native Fish in Play, Hold Redfin at Bay”. If you would like a copy sent to you contact aquatic.biosecurity@dpi.nsw.gov.au.

How you can help

- If you suspect redfin perch is being offered for live sale either in an aquarium or online (both being illegal in NSW) report it!

- Report any redfin perch sightings outside known range (see map above for known range)

- Don’t transfer redfin perch between waterways or introduce them into farm dams - it's illegal!

- Don’t use live redfin perch (or any other live finfish) as bait in freshwater - it’s illegal and can spread redfin to new areas.

- Don’t return redfin perch to the water – large redfin perch are good sport and eating fish and there are no bag or size limits on them. Any caught redfin perch should be humanely dispatched immediately - it is illegal to be in possession of a live redfin perch, and the catch can only be stored dead, such as on ice in an esky. For more information see Commonly asked questions by recreational anglers regarding the notifiable listing of redfin perch in NSW.

- Obtain a permit to stock fish – and buy fingerlings from a registered hatchery to prevent contamination with unwanted species.

- Prevent unwanted hitchhikers – check, clean, and dry boats and gear between waterways. Ensuring your boat and trailer are free of weed before re-launching can help avoid the possibility of spreading redfin eggs and juveniles.

- Assist efforts to restore our rivers (which can help native fauna to out-compete redfin and other pest fish), for example by taking part on a RiverCare or LandCare project or by conserving and restoring riparian vegetation on your own land.

- Take part in native fish restocking programs with your local angling group.

Redfin perch are listed as a notifiable species under Schedule 1 of the Biosecurity Regulation 2017. As such it is illegal to release (other than immediately at point of capture, which is discouraged), or to move, buy or sell, or be in possession of live redfin Perch. Heavy penalties apply for non-compliance.

Redfin perch are listed as a notifiable species under Schedule 1 of the Biosecurity Regulation 2017. As such it is illegal to release (other than immediately at point of capture, which is discouraged), or to move, buy or sell, or be in possession of live redfin Perch. Heavy penalties apply for non-compliance.